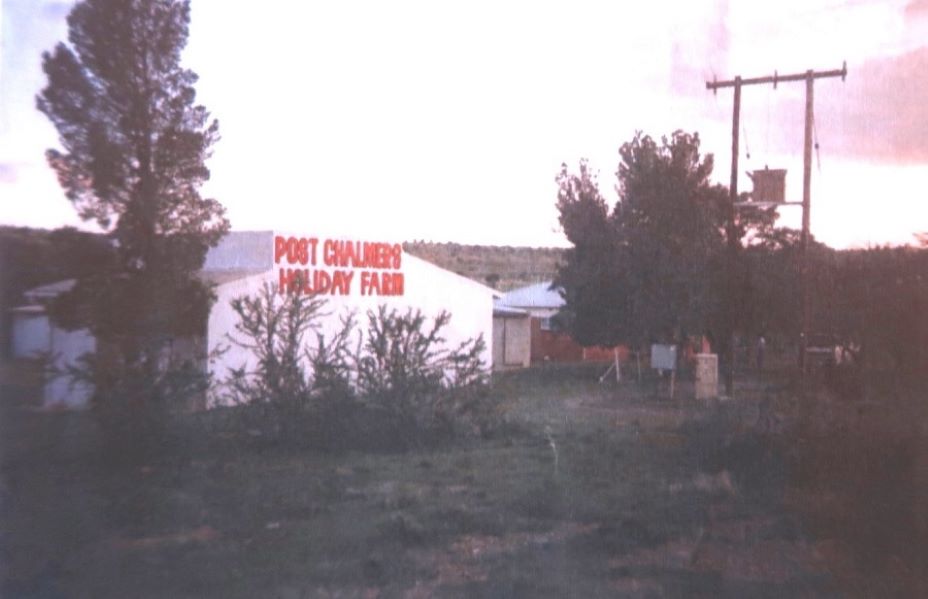

by marina geldenhuysMarina Geldenhuys reflects on her visceral response during a recent Holocaust study tour to Poland. Drawing from her research which looked at an apartheid-era 'death farm' in the Eastern Cape, Marina suggests that we instinctually search for signs and evidence of violence in places where violence occurred. THIS last July I visited Poland as a participant in the Poland Holocaust Study Tour 2022, organised by the Austrian Service Abroad, the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre and the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Cape Town. Although the Holocaust is not my area of study, I had spent my honours year absorbed in memory studies of violent histories. In particular my research looked at apartheid security police violence at Post Chalmers, a ‘death farm’ in the Eastern Cape. "We gathered for prayer at the grave of 800 murdered children and learnt that the executions started in the summer of 1942. Despair rose in my throat as I realised that, at the moment they died, the children saw what we were seeing, their minds probably attempting to reconcile the glade's beauty with its horror". There is a certain amount of crossover between violent histories – parallels and contrasts that are useful when considering how we confront these pasts. Memory studies informs an understanding that no matter how many books you read, there are some aspects of a history that can only be comprehended by placing your body in the physical spaces where that history played out. This understanding was affirmed in Poland, but I was surprised by the overwhelmingly sensory nature of my encounter with Polish history. My affective experiences catalysed a renewed engagement with my honours research, this time as ‘a participant’ rather than an observer. Post Chalmers is a small homestead in the Eastern Cape, situated on the R61 about 35 km west of the small town of Cradock, recently renamed Nxuba. I was raised in this town. My family moved there in 1985 when I was three-years-old. Despite its prominence in apartheid’s struggle history, the 'political' content of my childhood memory is limited to incidents of supply-hoarding by some white families prior to the 1994 elections. In a sense apartheid did not exist for white children of my generation. Before we could understand it, it was over, and the history syllabus (and our historical consciousness) fell victim to the protracted experiment of outcomes-based education. Some information about apartheid did filter through over time which kindled a desire in me to know more. Despite this, I did not learn about the dark history of Post Chalmers until I was thirty-five-years-old, when I found myself trembling with shock in a third-year lecture hall. I was taking a course with oral historian Sean Field called Memory, Identity and History. Field showed us Mark Kaplan's film, Between Joyce and Remembrance (2004). The film tells the story of Port Elizabeth (today, Gqeberha) student activist Siphiwo Mthimkhulu's detention, torture, poisoning and eventual murder at Post Chalmers in 1982. It produces a dark mirror between the wildly disparate experiences of apartheid for black activists and white activists; the black mother and the white mother; the black child and the white child. I was born in the same year as Mthimkhulu's son, Sikhumbuzo – the very same year that Mthimkhulu was murdered. When the location of the murder was displayed on screen, I experienced a seismic realisation that I had been to Post Chalmers. I recognised the name. I recognised the huge red painted signage against the exterior of the cell block – visible to all who drove between Cradock and Graaff-Reinet – and I recognised the interior of the cells. I knew, knew with my body, that I had been inside them. "The collision of this shadow-world of state-sponsored violence with my naïve memories of idyllic small-town life demanded a complete reframing of my childhood". I immediately phoned my father. He confirmed that we had spent a weekend at the farm in the early 1990s. In 1989, after Dirk Coetzee, co-founder and commander of the Security Police, started spilling apartheid's secrets, the state hurriedly sold Post Chalmers (and presumably many other sites like it). Unaware of its history, the farmer who bought Post Chalmers, André van Heerden, converted the buildings into guesthouses. Post Chalmers functioned as a 'holiday farm' until 1994 when it was exposed as a 'death farm' by 'Sergeant X', later revealed to be askari, Joe Mamasela. I had visited Post Chalmers as a child. The shock of this realisation allowed me to grasp that although I had intellectually engaged with apartheid at university, only now could I feel apartheid's proximity to my life. A seemingly insignificant childhood 'weekend getaway' suddenly mutated into a scene of horror. Knowledge of this violent history completely unmoored my sense of self. The collision of this shadow-world of state-sponsored violence with my naïve memories of idyllic small-town life demanded a complete reframing of my childhood. I consequently based my honours dissertation on Post Chalmers. The research helped me to reconcile my childhood memories with this painful history, and in the process, I became someone else. My research took the form of an oral history project which gave me access to some key interlocuters from Post Chalmers. Amongst others, I spoke to the current owner André van Heerden and his wife Ruby, and archaeologist Tim Hart, from the Missing Persons Task Team who worked on the forensic investigation in 2007. Poland reminded me of a crucial takeaway from those interviews. People with some form of knowledge of Post Chalmers' apartheid-era history were unsettled by the place. The key to their affective experiences was knowledge. We prepared for the Poland trip with a series of seminars and a reading list which equipped us with knowledge of the spaces we would visit. I finished my reading on the plane. From the moment I landed in Warsaw I suffered from a kind of vertigo. More than a simple unsteadiness, it felt like the ground beneath me was moving. Though I hadn't noticed, my travel companions claimed the flight had been turbulent and the landing rough. This explained the initial sensation, but the feeling persisted for the duration of our time in Warsaw. Warsaw is a strange city. The former ghetto is now covered with decaying Soviet-era apartment blocks. Sidewalks are littered and overgrown, and there is graffiti everywhere. We encountered very few people even during the week. After a day in these surroundings, with my persistent dizziness, a thought took hold that the earth was cursed and the city was rotting. On day two this thought intensified when we visited the Jewish Historical Institute housed in the former Main Judaic Library – its terrazzo floor still bearing witness to the inferno that crushed the ghetto uprising in May 1943. I was particularly affected inside the windowless exhibition halls and realised I was steadying myself against walls and displays. Though the Library, unlike the Great Synagogue that had stood next door, was not completely destroyed, an idea took hold that buildings in the old ghetto were suspended, literally, in the sense that they could not take root in this ruined earth. Having no physiological explanation for my vertigo, I suspect my body was attempting to 'make sense' of the city's troubled history in a similar way people had attempted to make sense of Post Chalmers. Ruby van Heerden had told me the story of an employee, Griet (last name not known) and her family who stayed at Post Chalmers for a short time. They soon asked to move to the van Heerden's other farmstead as they reported difficulty breathing at night. Ruby said she didn’t know if Griet and her family knew what had happened there, but they insisted the place was haunted and no other workers could be convinced to stay there. Ruby had a sensible explanation for the family's discomfort – they made fire indoors to cook on and keep warm, using the abundant Acacia wood on the premises. As Ruby explained, Acacia wood releases a gas when burnt which can cause dizziness. Upon further investigation I learnt that most Acacia species contain psychoactive alkaloids like dimethyltryptamine, more commonly known as DMT. Despite the potential presence of a hallucinogenic substance, I suspect the more powerful component of the family's experience was knowledge of the place. Ruby mentioned that there were rumours that something was not right at Post Chalmers, which accords with the fact that Griet lived at Post Chalmers shortly after Joe Mamasela implicated it as a 'death farm'. "By the end of the Poland tour I finally knew with my body what I had previously only understood intellectually. We look for signs of violence because we want and, perhaps unconsciously, need places where violence occurred to be obvious". Another Poland experience stirred at what I'd learnt during my research. On day five we arrived at Zbylitowska Gora, one of the largest of the many mass shooting sites saturating Poland. The forest glade was cool, protected from the heatwave by the tall trees. Sunlight filtered through leaves and reflected off the long grass, casting a vital green glow. The sound of cicadas humming along to birdsong enveloped us, and nearby we could hear children enjoying themselves on a BMX track. It was simultaneously ordinary, beautiful and devastating. We gathered for prayer at the grave of 800 murdered children and learnt that the executions started in the summer of 1942. Despair rose in my throat as I realised that, at the moment they died, the children saw what we were seeing, their minds probably attempting to reconcile the glade's beauty with its horror. We were given some time to gather ourselves and contemplate the space. I caught myself inspecting tree trunks for bullet holes. This was, of course, illogical. Some bullets almost certainly hit the trees but, unlike the pockmarked matzevot in Warsaw's Jewish cemetery, the bark would have healed, making the mark of violence invisible to my inexpert eye. I was doing exactly what civilian visitors to Post Chalmers had done in 1994. Joe Mamasela's confessions saw the arrival of busloads of curious visitors to the site to make sense of this place where activists were secretly murdered. The van Heerdens accommodated these visitors, allowing them to inspect every inch of the premises. Being the most recognisable spatial element testifying to the site's earlier brutal functioning, the cells drew particular interest from most groups. The van Heerdens recalled that visitors often interpreted red stains against the open-air cell walls as blood. They tried in vain to explain that these were the droppings of birds feeding on prickly pears. Even experts misconstrued material features of Post Chalmers as marks of violence. In 2007 archaeologist Tim Hart visited Post Chalmers in preparation for the Missing Persons Task Team (MPTT) investigation. The cells were converted to an abattoir in 1998, which, given its history, particularly unsettled Hart. He described seeing a furrow running from the abattoir carrying a mixture of water and blood to the nearby river. When I visited Post Chalmers in 2018 the van Heerdens explained that there had been a furrow for washing away animal dung, but that blood was directed into French drains underneath the abattoir. By the end of the Poland tour I finally knew with my body what I had previously only understood intellectually. We look for signs of violence because we want and, perhaps unconsciously, need places where violence occurred to be obvious. We want to know just by looking. When we don't find the signs of violence we expect, our bodies find ways of producing signs. The phrase 'make sense of' has a new meaning for me. It is no longer about logic or reason. Rather, it signifies the body's attempt to reconcile what we know with what we see. We are unsettled by the absence of physical signs of violence because it forces us to confront the possibility that violence can happen anywhere, and that any space where we find ourselves might contain a brutal past. Marina Geldenhuys is studying towards a Masters in Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town. She works at the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and the UCT Writing Centre.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|